Grief support

If you are grieving after a bereavement, supporting someone else or helping a child or young person coping with grief, you are not alone.

Our expert information and advice can help you or someone close to you cope with grief and deal with the practical issues after someone has died.

Bereavement information and advice

Our explainers, guidance, tips and stories will help you understand your thoughts and feelings as you learn to live with grief.

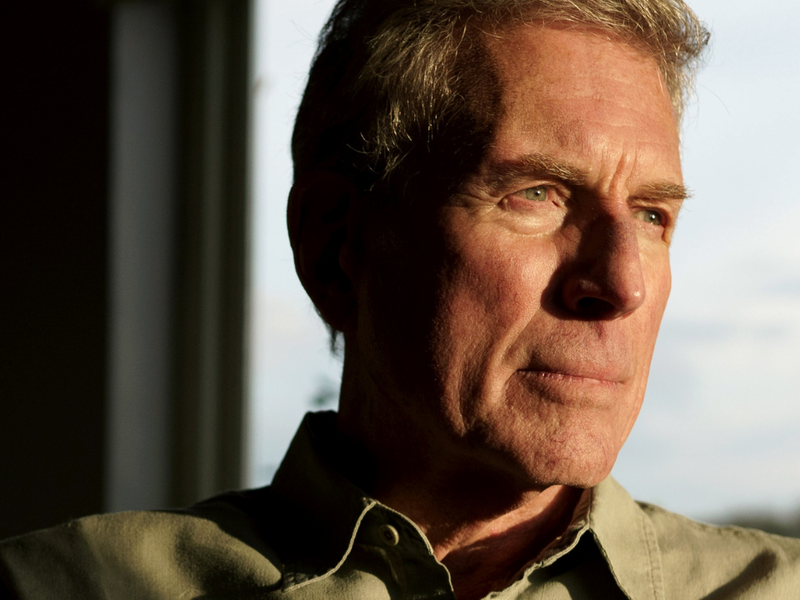

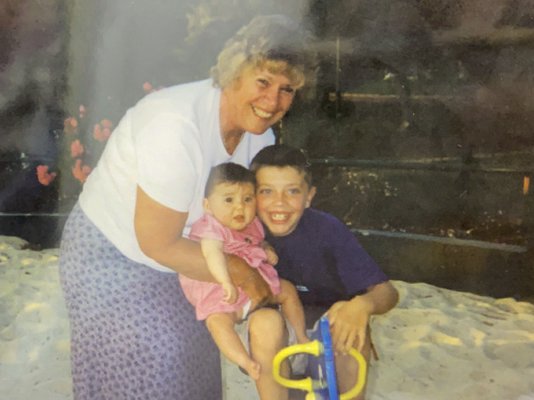

Grief is a journey – a journey without an end. You just have to keep moving forward and take the person that’s passed away along with you. I’ve learnt so much about grief from Sue Ryder in the past few years.

Read Debbie's story

Our grief support services

We’re here to connect you with the right support. Find out more about our free-to-access advice, information and resources.

More information on staying safe and warm after a bereavement